Shakespeare would have made a great movie writer.

—Orson Welles, stage and screen director

Shakespeare is no screen writer.

—Peter Hall, stage and screen director

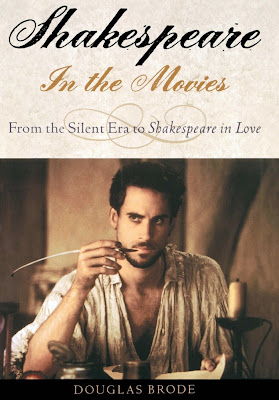

Shakespeare and the Movies

The above quotes, which illustrate the fact that two prominent directors of films based on Shakespearean plays can differ so drastically on the issue of Shakespeare's writing and the movies, make it clear we are wading into dark waters here. Shakespearean cinema is the only subgenre of narrative film that remains the center of an ongoing debate—not only among skeptical literary traditionalists but even those cineastes who make the movies—as to whether it has a right to exist. First, though, to dispose of the traditionalists: critic John Ottenhoff, reviewing Much Ado About Nothing for Christian Century in 1993, proclaimed his prejudice outright: "My complaints about the limits of [Kenneth] Branagh's film indicate only that no performance can substitute for the richness of reading, discussing, and meditating upon a text."

With the words no performance, Ottenhoff dismisses stage as well as screen, expressing a dominant twentieth-century bias toward the Bard. Although academia has, for the better part of our century, been populated by like thinkers, it's important to recall that Gentle Will would strongly disagree. His plays were written to be seen, not read—at least not by anyone other than the company performing them. They were never printed in his lifetime, probably according to his wishes. The plays were meant to be enjoyed in the immediate sense, not as removed literary works to be studied, like butterflies mounted by some eager collector who presses out all the lifeblood and mummifies beauty under glass.

Orson Welles and Peter Hall, however, are another matter. Both dedicated their lives to bringing the words from the page to the stage—and screen. Hall's line of argument derives from an understanding of the essential difference between live theater and motion pictures as storytelling forms. Film professor Louis Giannetti once claimed that a blind man at a play would miss 25 percent of what was significant, the same amount lost on a deaf person watching a film. Since the advent of the movies, in nonmusical plays the word is primary; in film, however, image dominates. Or, as Hall put it, Shakespeare "is a verbal dramatist, relying on the associative and metaphorical power of words. Action is secondary. What is meant is said." However right for live theater, "this is bad screen writing. A good film script relies on contrasting visual images. What is spoken is of secondary importance."

To a degree, Hall is right, particularly when he speaks of "contrasting visual images." Legendary director and film theorist V. I. Pudovkin asserted back in 1925 that "editing is the basis of all film art." What Peter Hall fails to take into account is that Shakespeare purposefully overwrote. Set design, costuming, special effects, and the like were not always well-represented in low-budget Elizabethan theater, which made it sometimes necessary for the writer to compensate for lack of production values by vividly describing everything. (from introduction of the book)

No comments:

Post a Comment